The administration’s funding cuts would force unaccompanied migrant children, from infants to toddlers to teenagers, to navigate complex and punishing legal procedures entirely alone.

Alexa Sendukas, managing attorney at GHIRP, preparing a 7-year-old client for his asylum interview.

(GHIRP)

The notice from the Department of the Interior arrived in the middle of the workday. Alexa Sendukas, a managing attorney at the Galveston-Houston Immigrant Representation Project, opened her inbox to a notice directing her to stop working immediately. The order was spare. In three paragraphs, the Trump administration halted all work under a government contract funding legal representation for unaccompanied migrant children. “The stop-work order,” the letter read, “is being implemented due to causes outside of your control.”

The order, sent on February 18, interrupted a busy week at GHIRP, with attorneys filing asylum applications ahead of an impending deadline. Harris County in Texas, home to Houston, receives the highest number of unaccompanied children in the country. The day the order was issued, one of Sendukas’s colleagues had just returned from representing two unaccompanied children in immigration court, two other attorneys had hearings the next day, and paralegals were still at a shelter providing legal orientation to newly arrived children.

Scott Bassett, a managing attorney with the Amica Center’s Children’s Program, says that the vast majority of children he works with are eligible for relief—yet requesting relief can be so complex that it’s nearly impossible to apply without legal representation.

Each year, GHIRP provides legal services to 1,500 unaccompanied children through federal funding. Currently, the Project is representing nearly 300 clients. “We were in the middle of a lot of work, and we had to pivot—because there really was no way to stop doing the work we were doing, especially for our clients,” Sendukas said.

GHIRP is among 89 legal services organizations whose work is funded through a government contract titled “Legal Services for Unaccompanied Children.” Attorneys like Sendukas provide legal screenings and “know your rights” presentations to children in shelters, as well as direct representation in immigration proceedings. Attorneys funded through the contract are currently representing as many as 26,000 unaccompanied children across the United States.

In February, the Trump administration issued the initial stop-work order; three days later, it reversed the order with no explanation. Then on March 21, the government canceled key sections of the contract, pulling funding for all direct legal representation. On April 29, a judge issued a preliminary injunction temporarily extending funding through September—but the Trump administration is aggressively appealing in an effort to immediately stop funding.

In the months since the March 21 contract termination, nonprofits across the country have laid off attorneys and prepared to shutter programs for unaccompanied children. Adina Appelbaum, program director of the Immigration Impact Lab at the Amica Center for Immigrant Rights, describes the cuts as the most devastating blow to the rights of migrant children since Trump’s family separation policy.

Current Issue

“This is really the only protection available for these unaccompanied children who are already separated from parents. Because they’re unaccompanied, their lawyers are the only person they have to advocate for them and their best interests and rights in the system,” Appelbaum told me. “This case is really about the government sadly attacking one of the most vulnerable groups of children in the world.”

The attacks on legal representation come amid other escalating threats to unaccompanied children. In some courts, the government has accelerated removal proceedings against unaccompanied children, a tactic known as “rocket dockets.” An internal Immigration and Customs Enforcement memo from this year ordered agents to track unaccompanied children and their sponsors, and in recent months, ICE has ramped up visits to the residencies of unaccompanied children—an increase Sendukas has observed first hand with children she works with in Houston.

These moves amount to a comprehensive attack on the rights of unaccompanied children, depriving them of legal counsel and representation in the moment they may need it the most. Without access to representation, children, from infants to toddlers to teenagers, will be forced to navigate complex immigration proceedings and possibly face deportation, entirely alone.

Ana Devereaux, a managing attorney at the Michigan Immigrant Rights Center, has a doll set she uses when working with very young children. A wooden box conceals a miniature court scene with painted wooden people, just inches tall. A toy judge, flanked by a clerk and an interpreter, wears black robes. His nose is a dot of paint, his mouth a benign U-shaped smile. The judge faces two sets of seats: to his right, a table for the ICE attorney who is prosecuting the child; to his left, a table for the immigrant child defendant and their legal counsel. In reality, that chair for counsel can be empty.

Unlike defendants in criminal proceedings, migrants facing deportation are not entitled to legal representation. Immigration law is infamously complex; lawyers often say it is second only to tax law in its impenetrability. Navigating the annals of immigration law can be a challenge for trained attorneys—and virtually impossible for a child. Some unaccompanied children are so young their feet do not touch the courtroom floor; some have not yet learned to speak.

Without legal counsel, these children are expected to represent themselves. “Children will be going to immigration court in a system that, in theory, is supposed to be set up to honor their rights, to allow for due process,” Devereaux said. “It will be a complete sham. There’s no meaningful way they can access that—no possibility of due process if they don’t have access to counsel.”

When unaccompanied children arrive at the US-Mexico border, they are usually detained by Customs and Border Protection. Within 72 hours, the child must be transferred to the Office of Refugee Resettlement. Children are then held in ORR-run shelters until they are released to the foster care system or matched with a sponsor, usually a family member, with whom they can live.

Until 2002, detained unaccompanied children were overseen by Immigration and Naturalization Services, the precursor to ICE. That year, the Homeland Security Act transferred custody of children to the ORR, which is under the Department of Health and Human services. The move, a result of years of work by immigration rights advocates, was designed to better protect children from trafficking and abuse, and help children find sponsors who can take them out of ORR-run shelters without fear of punishment or deportation.

In 2008, a landmark anti-trafficking bill required that unaccompanied children receive legal representation to the “greatest extent practicable.” Four years later, Congress made funding available for attorneys devoted to representing unaccompanied children. Over the past decade and a half, Congress has repeatedly expanded that funding: In 2024, Congress allocated over $5 billion to nonprofit legal organizations providing legal services to unaccompanied children.

Attorneys like Devereaux and Sendukas can serve children in multiple capacities. Attorneys visit ORR shelters to give “know your rights” presentations and legal screenings. The first step is explaining what it means to be an “unaccompanied alien child” and sorting through complex, English-language forms children might have received while in CBP custody. If a child is released from a shelter to live with sponsors or in long-term foster care, attorneys can directly represent them in court as they seek protection.

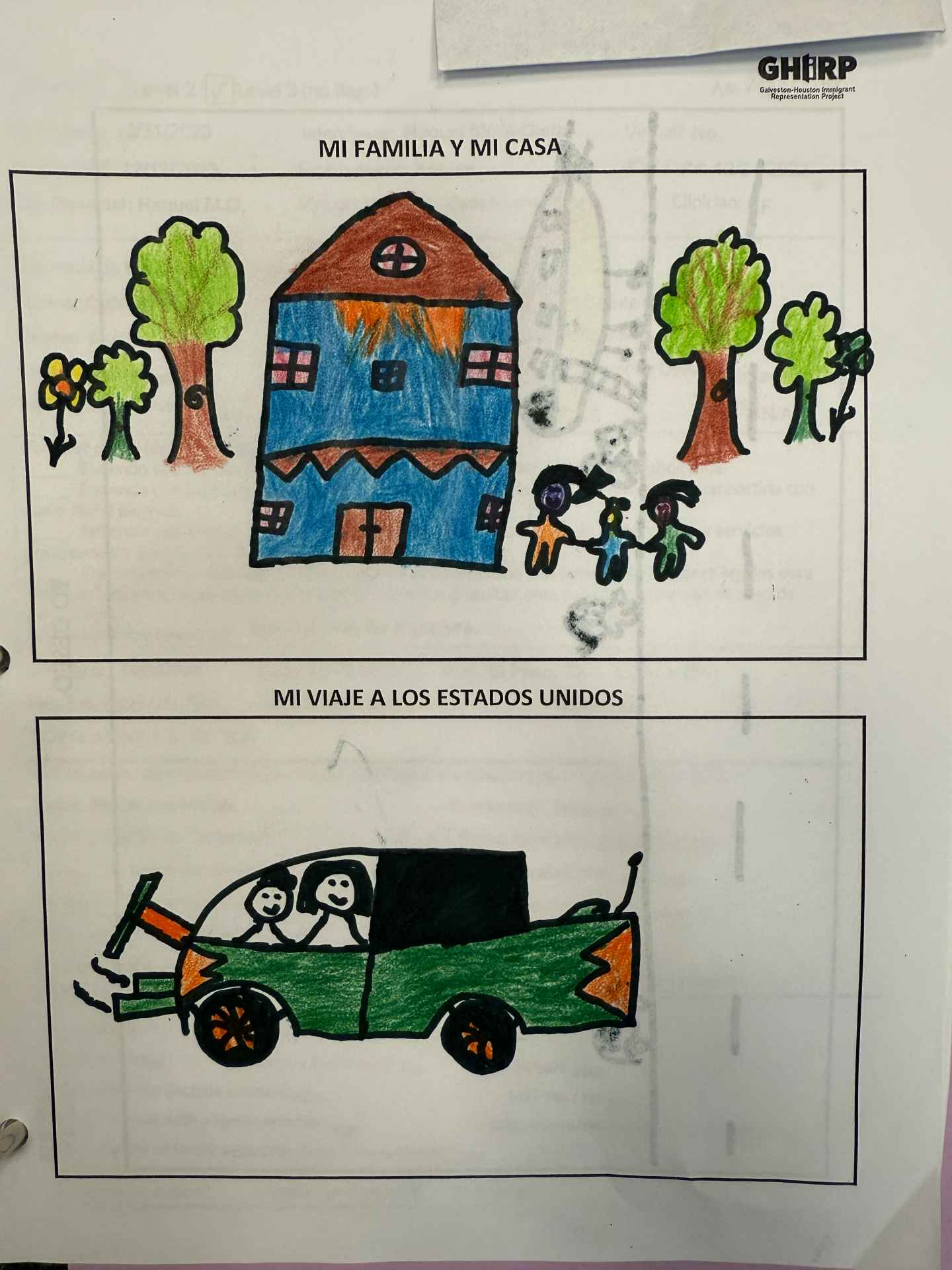

Representing young children requires a special set of skills, extending beyond the courtroom. Sendukas considers being a children’s attorney its own legal “specialization.” Attorneys will use coloring books, games, and songs to help explain complicated legal processes. Ideally, an attorney will meet with a child several times to build trust. Some attorneys have children draw pictures of their home country to better understand their case for asylum; some use fidget spinners and Play-Doh to keep children engaged.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →

Legal representation can dramatically change a child’s outcome in immigration court. A congressional report analyzing data from 2005 to 2017 found that 84 percent of unaccompanied children without legal representation received a removal order; less than 1 percent received any sort of immigration relief. For children with representation, only 21 percent received a removal order.

Attorneys also serve as an important check on conditions at shelters. In 2023, news broke that a counselor at the ORR facility in Grand Rapids, Michigan, run by Bethany Christian Services had sexually abused teenage boys living in the shelter. MIRC met with victims to make sure they knew their rights and had representation if they decided to speak with law enforcement and press chargers.

But if this situation had occurred during a time without the unaccompanied minors contract, Devereaux says, with no attorneys regularly visiting ORR shelters, instances of abuse inside shelters for unaccompanied children could pass unnoticed by anyone outside, and without help on their visa applications, victims could be subject to deportation. “I expect, through occasional bad actors and just systemic failures, that those children will suffer significant violations of their rights in custody,” Devereaux told me.

On Friday, March 21, Sendukas felt sick. She took a NyQuil and went to sleep. She woke up to a flood of e-mails, texts, and calls with the same piece of news: The Trump administration had abruptly canceled key portions of the unaccompanied children’s contract.

A panic jolted the network of legal nonprofits across the Houston area, and coast to coast. The administration had terminated all contract funding for direct representation. The cancellation provided no wind-down funding, ordering attorneys to stop all direct representational work immediately.

GHIRP immediately began operating off reserve funds and laid off around half of its team handling immigrant children and youth. MIRC, Devereaux’s employer, laid off around 72 employees in the wake of the cancellation.

In late April, a judge restored the funding via preliminary injunction. Yet, because the injunction only temporarily reinstated funding—and the Trump administration is likely to pursue a rehearing in the Ninth Circuit or appeal to the Supreme Court—neither organization has been able to restore their legal teams to previous levels.

Appelbaum fears that the Trump administration’s attacks on attorneys may lead to a massive, long-term loss of experience in the field. The Amica Center already struggles to find lawyers to do the emotionally difficult work. Even if the funding is restored under a different administration, she predicts they will “essentially lose all expertise in the field.”

Jennifer Podkul, chief of global advocacy at the nonprofit Kids in Need of Defense, similarly fears the long-term consequences for children. “I feel like I’ve aged 20 years in three days,” Podkul told me when we spoke last February, shortly after the stop-work order had been rescinded.

“We built up systems of experts in protecting the needs of unaccompanied children, and the loss of this contract could create utter devastation to this network that’s been built up, of really whip-smart, committed attorneys who are there every step of the way in this complicated process for kids,” she said.

Currently, Sendukas’s youngest client is 2 years old. For Sendukas, leaving this work feels impossible. But if the Trump administration succeeds in cancelling the contract, continuing may become impossible too.

Maggie Grether

Maggie Grether was a 2024 Puffin student writing fellow for The Nation. She served as the co-editor-in-chief of The New Journal at Yale University, where she also collaborates with the Investigative Reporting Lab at Yale.