Rediscovering Reform: Five Forgotten Leaders Who Could Inspire a New Political Era

As the second half of the 2020s unfolds, American politics stands on the brink of generational change. The advanced age of leading figures—from Joe Biden’s evident decline to enduring questions around Donald Trump’s health and cognition—mirrors a broader crisis of leadership. A gerontocratic Congress, punctuated by deaths in office, only underscores the urgent need for new blood in both major parties.

While Republican reform remains stalled under Trump’s influence, the progressive future is also clouded. Democrats appear adrift—fragmented between personality-driven coastal enclaves and a shrinking working-class base that increasingly doubts their ability to govern effectively. Many progressives, preoccupied with the nation’s moral failures, struggle to craft a hopeful, unifying vision. This has led to a kind of historical amnesia, one that discourages learning from past leaders who once navigated similar political and economic storms.

This Memorial Day, it’s worth revisiting five independent-minded public servants—some Democrats, some Republicans—whose ideas and integrity offer lessons for a new generation of political reformers.

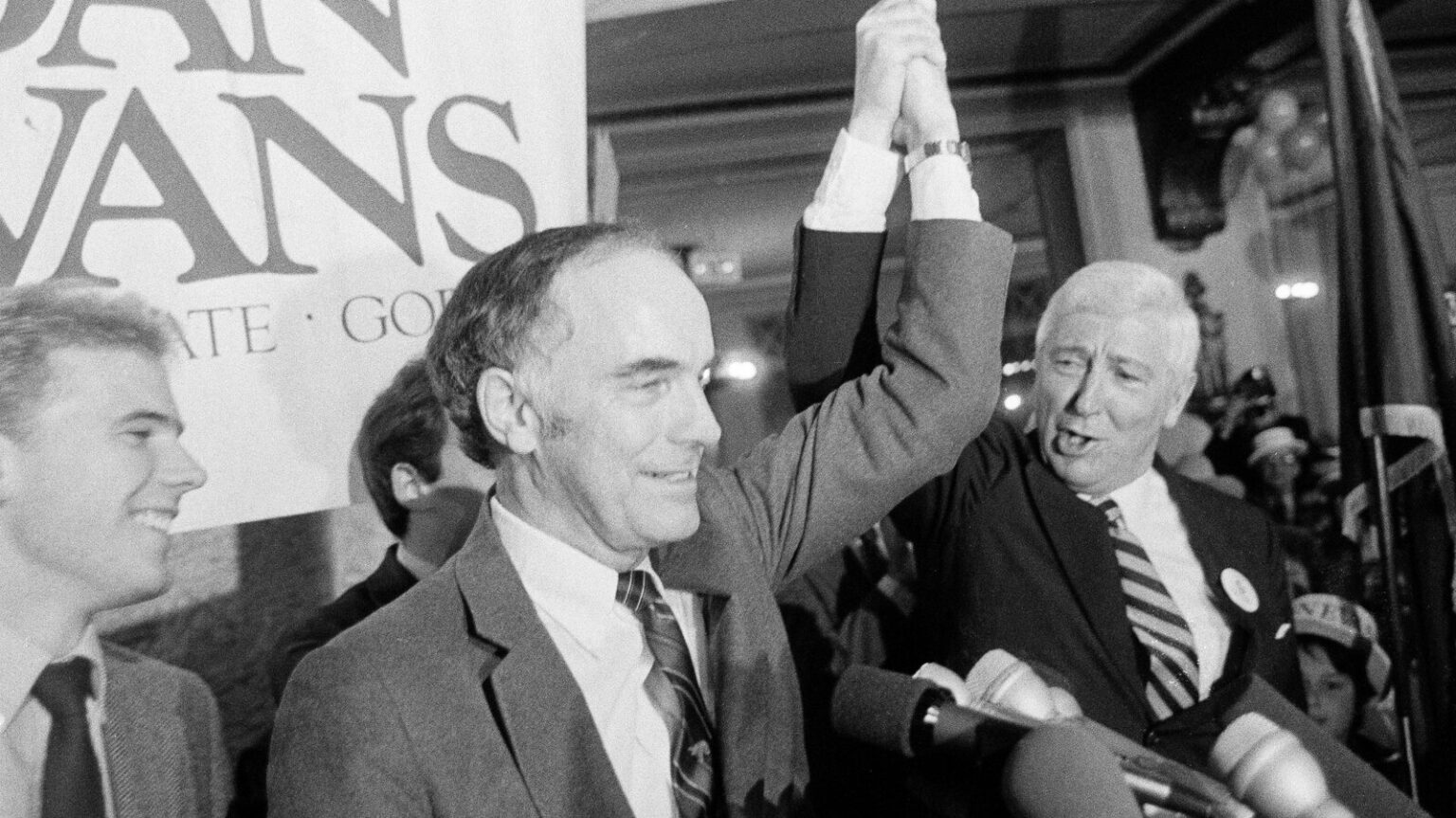

Daniel J. Evans (1925–2024)

A three-term Republican governor of Washington and later U.S. Senator, Evans died in 2024 with little national notice. But in the 1970s, he stood out as a model of constructive Republican pluralism—an alternative to the rising Goldwater-libertarian wave. He expanded social services, pioneered environmental policy with the nation’s first Department of Ecology, championed nuclear power, and opened doors for women and minorities.

Today, Evans’s agenda reads like a progressive platform. Yet he wasn’t a closet liberal—he simply believed government should solve problems. Rather than dogmatically opposing “big government,” Evans addressed real economic and social challenges, setting an example for both parties. Republicans in blue states could study his pragmatic, inclusive approach. For Democrats, his record serves as a reminder that results—not rhetoric—build trust. Most notably, Evans demonstrated that environmental protection and economic growth are not mutually exclusive.

Silvio O. Conte (1921–1991)

A Republican congressman from Massachusetts, Conte entered politics after being sidelined by the local Democratic machine. That early rejection proved strategic—his outsider status gave him more influence in the House. He became a fierce advocate for workers in his manufacturing-heavy district, while also supporting civil rights, environmental legislation, and NIH funding through the Reagan era.

Conte belonged to the “Gypsy Moths,” moderate Republicans who resisted Reagan’s deep cuts to urban aid. His commitment to federal investment in public health and struggling regions contrasts sharply with today’s GOP leadership. But progressives, too, should take note. Conte’s enduring popularity came from staying rooted in his working-class constituency—not viral posts or celebrity politics. His legacy is a blueprint for winning back the trust of the Rust Belt.

Fred R. Harris (1930–2024)

A Democratic senator from Oklahoma and briefly a presidential contender, Harris evolved from Great Society loyalist to left-populist firebrand. After opposing the Vietnam War, he left the Senate to launch a grassroots movement he called the “New Populism.” While his 1976 presidential bid faltered, Harris was ahead of his time—warning against concentrated economic power and championing broad-based reform.

His vision ultimately failed to unite a party splintered by race, war, and class tensions. Yet Harris anticipated today’s anti-monopoly revival and the resurgence of populist politics. As younger reformers seek to rebuild economic democracy, they’d do well to study where Harris succeeded—and why he fell short.

Ernest F. “Fritz” Hollings (1922–2019)

A long-serving senator from South Carolina, Hollings defied easy categorization. Initially resistant to civil rights, he later oversaw peaceful desegregation at Clemson University and embraced anti-poverty programs. By the 1980s, he became one of the Senate’s fiercest critics of globalization.

Unlike many Southern politicians, Hollings challenged free trade orthodoxy, warning that unchecked outsourcing would hollow out the industrial base. Some of his rhetoric now echoes MAGA themes, but Hollings was no nationalist demagogue. He advocated for smart trade policy, antitrust enforcement, and manufacturing as pillars of national strength. His legacy complicates the myth that economic nationalism belongs exclusively to the right—and offers a playbook for progressives who want to reconnect with disaffected workers.

Vance Hartke (1919–2003)

A liberal senator from Indiana, Hartke was a key architect of Medicare and Medicaid, and among the earliest critics of the Vietnam War. But he also deserves credit for sounding the alarm on deindustrialization. In the early 1970s, Hartke pushed for tough import controls and industrial policy to protect America’s manufacturing base—positions mocked at the time but increasingly prescient.

He worried not just about lost jobs but the erosion of technical expertise and regional capital. “Quality cameras, portable radios, electronic calculators and many other items are no longer produced in this country at all,” he wrote in 1972. Though his protectionist proposals were rejected, Hartke’s foresight raises an important question: What if America had heeded his warnings before it was too late?

Why These Leaders Still Matter

None of these men were perfect. Some failed in their ambitions; others compromised in ways we might now criticize. Yet what unites them is their refusal to simply follow the crowd. They stood for principle over party, action over ideology, and inclusion over inertia.

For progressives trying to escape the defeatism of the 2010s and 2020s, their examples are invaluable. Between Evans’s technocratic pluralism and Harris’s populist idealism lies a path forward—one that prizes public service, meets real-world needs, and builds coalitions rooted in shared purpose rather than tribal identity.

In a time of brittle institutions and calcified leadership, their stories remind us that principled independence isn’t weakness—it’s where reform begins.